GPS tracking with sports watches and smartphones – technology, accuracy, and tips

Here we explain as clearly as possible what GPS is all about, what different satellite systems there are, and how current devices deliver increasingly accurate data thanks to dual-band GNSS and sensor fusion. We also look at the differences between smartphones and sports watches when it comes to tracking, typical sources of error (keyword: GPS drift), and give tips on how to interpret GPS data correctly. The aim is to show both tech-savvy and athletically active readers what is important for good GPS tracking.

What is GPS and what is GNSS?

The term GPS is often used colloquially to refer to any satellite navigation system, but it actually refers to the Global Positioning System developed by the US military. GPS is therefore just one of several global navigation satellite systems – collectively referred to as GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System). In addition to GPS (USA), there are Galileo (Europe), GLONASS (Russia), and BeiDou (China) as further GNSS constellations. Each of these systems operates a fleet of satellites that orbit the Earth and transmit navigation signals.

Modern receivers around the world often receive signals from multiple GNSS systems simultaneously to determine their position. For example, a smartphone typically uses GPS and Galileo (and often GLONASS/BeiDou) in parallel—this is referred to as multi-GNSS. This combination increases the number of visible satellites in the sky, resulting in better coverage and accuracy. GNSS is therefore the umbrella term, with GPS being a single system under it. To understand this:

GPS (USA): Ältestes GNSS, seit 1978 in Betrieb, heute ca. 30 aktive Satelliten. Weltweit verfügbar, zivile Standardgenauigkeit ca. 5 m im Normalbetrieb, mit modernen Dual-Band-Empfängern <1 m möglich.

Galileo (EU): Europäisches System (voll operativ seit 2016) mit ~30 Satelliten. Bietet von Anfang an Dual-Frequenz-Signale für höhere Präzision (teils <1 m) und ist speziell für zivile Anwendungen optimiert.

GLONASS (Russia): Russian system (24+ satellites). Slightly lower individual accuracy than GPS, but robust, especially in northern latitudes (thanks to orbital inclination) and, when combined with GPS, a valuable addition in difficult areas.

BeiDou (China): Newest system (global expansion ~2020, over 45 satellites). Leading in Asia-Pacific and increasingly integrated worldwide. Offers special functions (messaging) in addition to positioning, but is particularly interesting in combination with other GNSS systems.

GPS vs. GNSS: While GPS is often referred to colloquially, today's sports watches/smartphones mostly use GNSS multi-constellation. This means that they receive signals from GPS and Galileo in parallel, often also GLONASS and BeiDou, in order to achieve the best possible positioning. As a result, you still see coordinates (latitude/longitude) on the device—but the data base is broader and more fail-safe than in the days when only GPS was available.

How does GPS work technically?

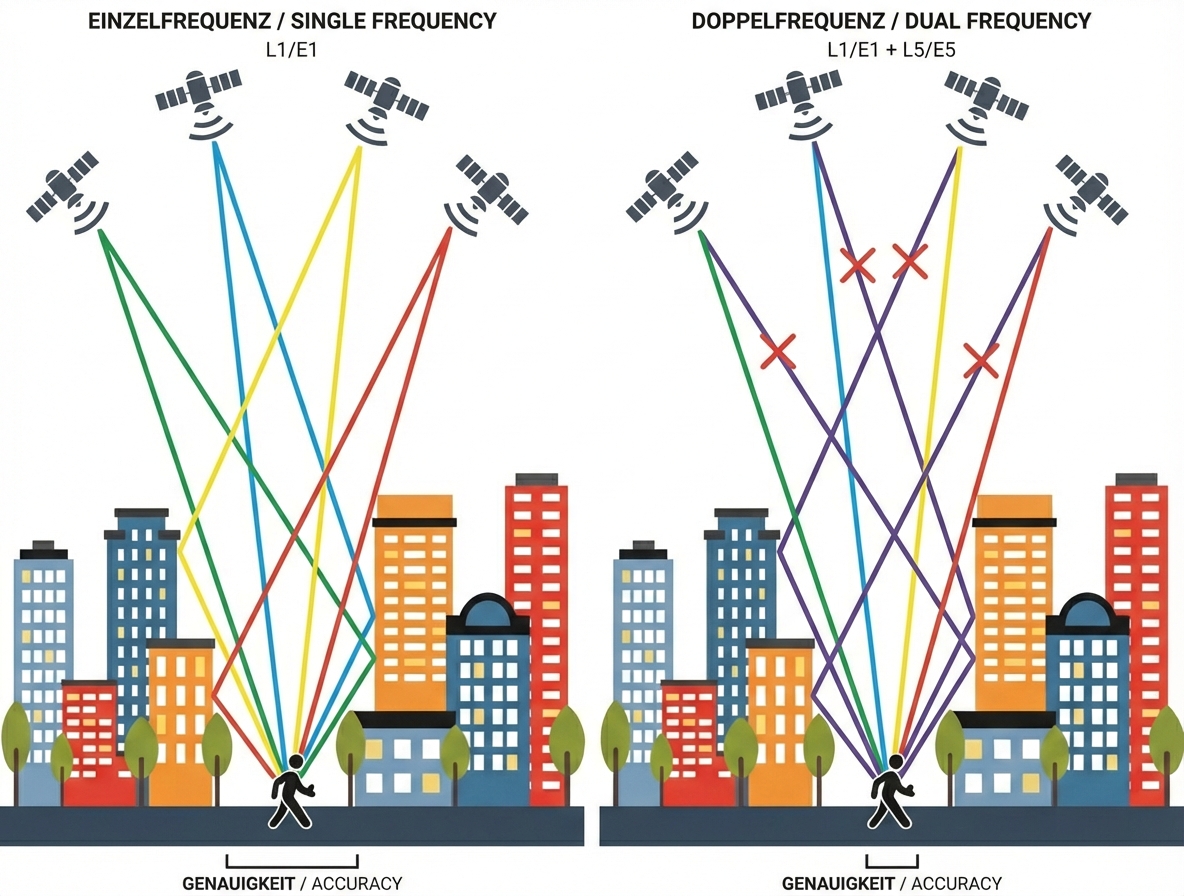

The technical functionality of GPS positioning is based on precise time measurement and geometry. In principle, satellites continuously transmit radio signals with coded time stamps and their orbital information. A GPS receiver (e.g., in a watch) receives these signals and measures the transit time: From the transit time c (multiplied by the speed of light), it calculates the distance (pseudorange) to the respective satellite. Since the signal travels at the speed of light (~300,000 km/s), the time measurement requires atomic clock-accurate synchronization. GPS satellites therefore have atomic clocks on board, and the receiver synchronizes its internal time with the satellite signals.

Trilateration: If you know the distance to a satellite, you are somewhere on the surface of an imaginary sphere around that satellite (radius = distance). With three satellites, two possible positions can theoretically be determined (intersection of three spherical surfaces) – one of which can be discarded, as it is usually far outside the Earth's atmosphere. However, the receiver must also take its own clock deviation into account. In practice, therefore, at least four satellites are needed to uniquely determine the 3D position (latitude, longitude, altitude) and time correction. Three satellites provide the horizontal position (2D) plus synchronization, with a fourth adding the altitude (3D fix). Modern receivers often use signals from far more than four satellites (frequently 8-12 or more simultaneously) by statistically combining the additional measurements via mathematical compensation methods (least squares, Kalman filter). This increases accuracy because measurement errors are averaged and the geometry of the satellites is better taken into account.

Coordinate system: The device typically outputs the calculated position as geographic latitude and longitude based on an Earth coordinate system. The common reference system for GPS is WGS84 (World Geodetic System 1984) – a global coordinate system referenced to an Earth ellipsoid. All GPS satellites transmit their orbital parameters and position data in this reference system, enabling receivers worldwide to provide consistent coordinates in degrees. Example: Typical GPS tracking displays points as WGS84 coordinates, which are then projected onto maps (e.g., in the sports watch app or Google Maps).

Single-band vs. dual-band GPS/GNSS

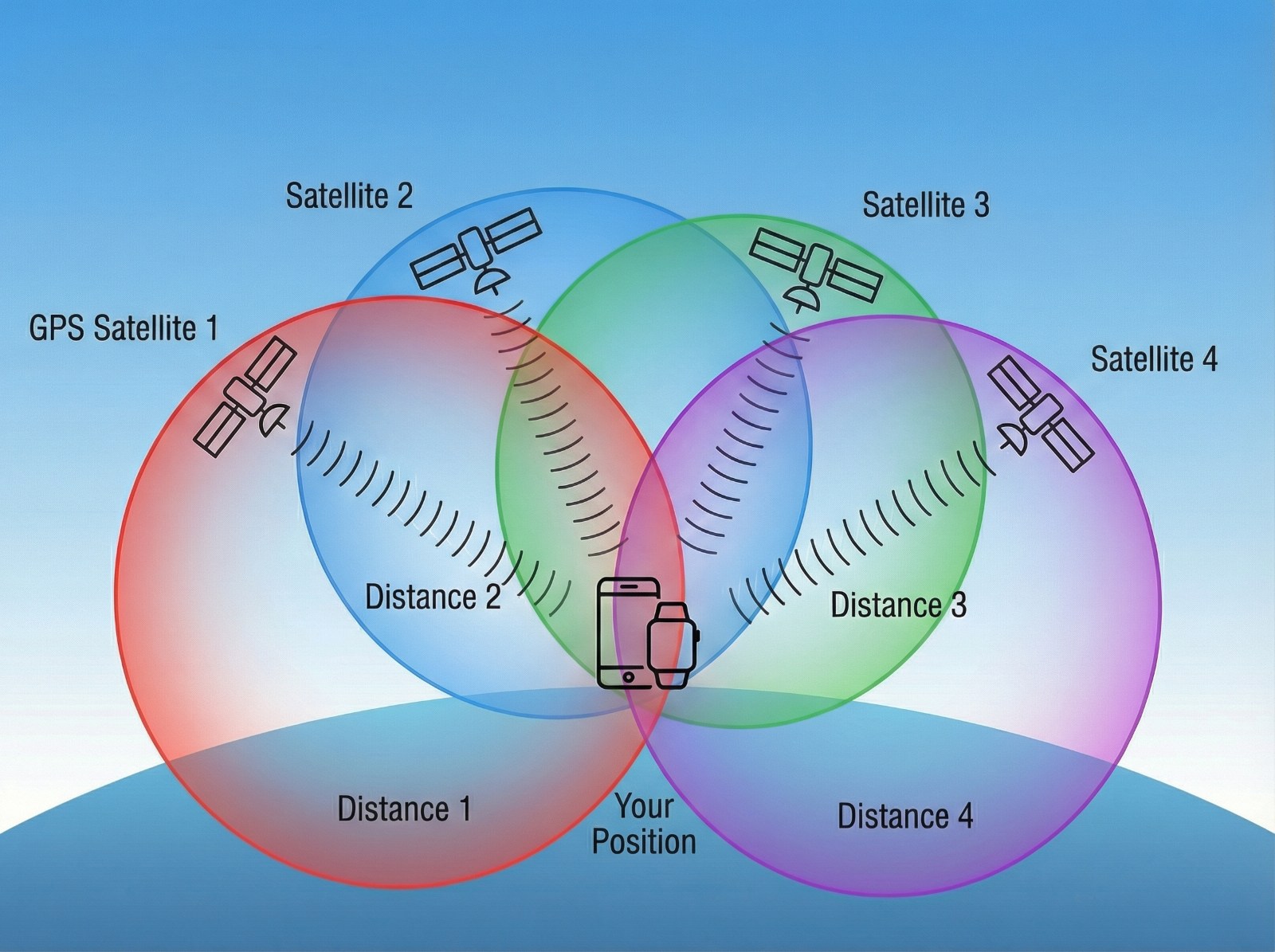

GPS was originally operated with a single frequency for civilian users (L1). Single-band GNSS receivers therefore only use one frequency band per satellite system – typically the L1/E1 band (~1.575 GHz), on which GPS and Galileo transmit their main signals for civilian users. Dual-band GNSS, on the other hand, can evaluate two frequencies in parallel, usually L1/E1 and L5/E5 (in Galileo, for example, E5a at ~1.176 GHz). Why is this important?

Ionosphere correction: On their way to Earth, the signals pass through the ionosphere, which affects the transit time depending on the frequency (refraction and delay). With only one frequency, the receiver can only estimate this error using rough models. With two frequencies from the same satellite, the transit time difference can be measured directly, allowing the ionosphere's influence to be largely calculated out. This significantly increases the basic accuracy, as a major error factor is eliminated. For this reason, professional GNSS devices have long been using dual- or multi-frequency technology – however, this used to cost several thousand euros. Today, dual-band chips are finding their way into consumer devices.

Multipath effects: In urban canyons or narrow valleys, satellite signals can be reflected by buildings, rock faces, or even dense ground coverings and arrive at the receiver with a time delay. The receiver then receives "ghost signals" in addition to the direct signal, which leads to position deviations. A dual-band receiver can handle such situations better: modern GPS chips listen to the same satellite signal on two frequencies, thereby receiving more information to detect and filter out multipath effects. The different frequencies penetrate or reflect environments differently in some cases – comparing both helps to identify incorrect runtime measurements. The result: in difficult environments (large cities, forest gorges), the position remains more stable with dual-band and jumps less, while single-band can often shift the track.

Schematic representation of single-band vs. dual-band GNSS in the city. On the left, the receiver only uses L1 signals – reflections from buildings (red lines) lead to distorted distance measurements and an inaccurate position (red area). On the right, with dual-band (L1 + L5), additional signal information can be evaluated and faulty signals detected (red X). The position accuracy (green area) is significantly higher because the receiver is better at excluding multipath signals.

The European Galileo system transmits on dual frequencies (E1 and E5a) as standard for all users. GPS has also started L5 signal operation (fully expanded from around 2021). Many newer sports watches and smartphones support this multiband use. Example: The first smartphone with dual-band GNSS was the Xiaomi Mi 8 in 2018; dual-band chips are now standard in almost all current high-end GPS devices.

Disadvantages: Dual-band GNSS requires more hardware and consumes slightly more power. For this reason, some sports watches offer a configurable multiband mode that can be activated as needed. However, when this mode is switched on, battery life is often noticeably reduced. Thanks to advances in chip efficiency and features such as Garmin's SatIQ (automatic switching between GNSS modes), this problem is becoming less of an issue. In everyday use, you can activate dual band for a city marathon or trail run in dense forest, for example, and switch it off in simple conditions to save battery power.

Sensor fusion: When GPS meets barometers and other devices

GPS alone already provides a great deal of data—but modern sports watches and smartphones do not rely solely on satellite signals. They combine them with other onboard sensors to obtain a more complete and accurate picture of movement. This sensor fusion typically includes:

- Barometer (altimeter): A barometric pressure sensor measures air pressure and can use this to derive altitude changes with great sensitivity. This is much more accurate than altitude measurement via GPS, which is susceptible to noise. High-quality devices therefore use the barometer for altitude recording accurate to the second, ensuring that the altitude profile is smooth and realistic. GPS is used in the background for auto-calibration: at regular intervals, the device checks the barometric altitude against the absolute altitude determined by satellite in order to correct for slow drift due to weather changes. This fusion combines the best of both worlds – the barometer accurately reflects relative up/down movements (e.g., it can detect an altitude change of a few meters), and the GPS ensures that the absolute altitude value is correct in the long term and is not distorted by air pressure fluctuations. The result: highly accurate total altitude meters and realistic altitude profiles, which is especially important for mountaineers.

- 3D acceleration sensor/gyroscope: Acceleration sensors (often 3-axis, including gyroscope) are built into virtually all smartphones and sports watches. They detect movements, rotations, and vibrations of the device. The tracking system can use this data to count steps, determine step frequency, or detect changes in direction, for example—independently of GPS. A gyroscope detects rotational movements; this allows the watch to "sense" when you turn or orient yourself, even if the GPS signal is temporarily weak. Some manufacturers make specific use of this feature: for example, newer running watches have special track mode algorithms that use motion sensors to detect when you are running on a curve on the track in order to correct the GPS there. Even in the event of a brief GPS failure (tunnels, dense city centers), the system can bridge the gap using inertial measurement. A well-known example is Suunto's FusedTrack technology: when the GPS interval is reduced (to save battery power), the movements in between are reconstructed using an acceleration sensor so that the track remains fairly accurate.

- Compass (magnetometer): An electronic compass that uses the Earth's magnetic field is also often found on board. This sensor is particularly helpful for map navigation—it shows the direction you are currently looking or moving in. It is not necessary for the actual position calculation, but in conjunction with GPS, it enables, for example, a map display on the watch to align correctly with the direction of travel, even when standing still (GPS can only derive direction from movement).

This sensor fusion makes tracking data more stable and meaningful. Take altitude measurement, for example: GPS alone would often produce altitude noise of tens of meters (a GPS receiver standing still tends to "wander" in altitude readings by ±15 m). With barometer support, on the other hand, the altitude profile looks smooth and small hills are recorded realistically. Thanks to sensors, the watch also notices when you continue running in a tunnel, for example (the acceleration sensor counts steps, the gyro maintains the direction), and can thus continue the position more plausibly at the tunnel exit instead of generating an outlier. All these aids ensure that sports watches in particular are often more reliable than the simplest GPS loggers in terms of track quality. High-end models (Garmin Fenix, Coros Vertix, Apple Watch Ultra, etc.) use automatic calibration and sensor fusion without the user having to intervene—the device constantly adjusts the barometric altitude, for example, and compares GPS and motion sensor data with each other.

GPS tracking: sports watch vs. smartphone – what are the differences?

Many people simply use the smartphone in their pocket to record their activities, while others swear by dedicated GPS sports watches or bike computers. How do smartphones and special sports watches differ in terms of GPS tracking quality? Here are the most important points:

- Antenna and housing: Special GPS devices (sports watches, trackers) often have larger, high-quality antennas that are specifically positioned for optimal satellite reception (e.g., on the edge of the watch or at the top of the device). Due to space constraints, smartphones only have small, all-purpose antennas and are often carried in a pocket or held in the hand, which can attenuate the signal. A watch on the wrist with a view of the sky tends to have reception advantages here.

- GNSS chipset: Sports watches usually use specialized GNSS chips that are optimized for accuracy (and energy-efficient continuous operation). Smartphones tend to use combined chipsets in their SoCs, which are also very capable, but often prioritize energy efficiency over maximum precision. In addition, current premium watches often support multi-band GNSS, which is not (yet) standard in all smartphone models.

- Software algorithms: The firmware of sports watches is designed to filter and smooth GPS data for sporting purposes. Manufacturers invest heavily in optimization algorithms to remove outliers and calculate distances accurately, for example. Dedicated GPS devices sometimes use very sophisticated filters and Kalman filter techniques. Smartphones often rely on the basic system (Android/iOS Location Services), which is more general in nature. For energy-saving reasons, position updates may be less frequent or strong data filters may be used, which can reduce accuracy. In short: a sports watch "knows" that you are probably following the route on your running track, for example, and could smooth out small GPS jumps, while a simple tracking app may show more noise.

- Data sources (A-GPS & Co.): Smartphones use additional location data such as Wi-Fi networks, Bluetooth beacons, or cell towers to improve or determine location more quickly. Assisted GPS (A-GPS) provides the initial position and time via the internet, which speeds up satellite fixation. During tracking itself, the mobile app can also incorporate Wi-Fi signals in cities, for example. Sports watches without a mobile connection, on the other hand, rely solely on GNSS satellite data (apart from the initial A-GPS download via a paired smartphone). This gives cell phones an advantage in city centers when it comes to fast initial fixes and allows them to estimate the position using networks when stationary. However, this auxiliary data plays a lesser role in continuous recording (outdoors with good reception).

- Interference and reception: Differences can become apparent in difficult environments (see next section on sources of error). A watch with a powerful antenna on the top of the wrist often still receives sufficient satellite signals even on winding trails or in dense forests, while a smartphone in a back pocket is more shielded and may "lose" the signal more often. In urban canyons, however, both types of devices are challenged – here, those with multi-GNSS and dual-band on board have an advantage. Some tests show that more specialized outdoor watches are somewhat more robust against interference. On the other hand, smartphones can sometimes still display a position (albeit inaccurately) despite weak GPS reception thanks to the aforementioned auxiliary data. Overall, the following applies: open sky = both good; borderline reception = slight advantages for high-quality sports devices, as these were developed for precisely such scenarios.

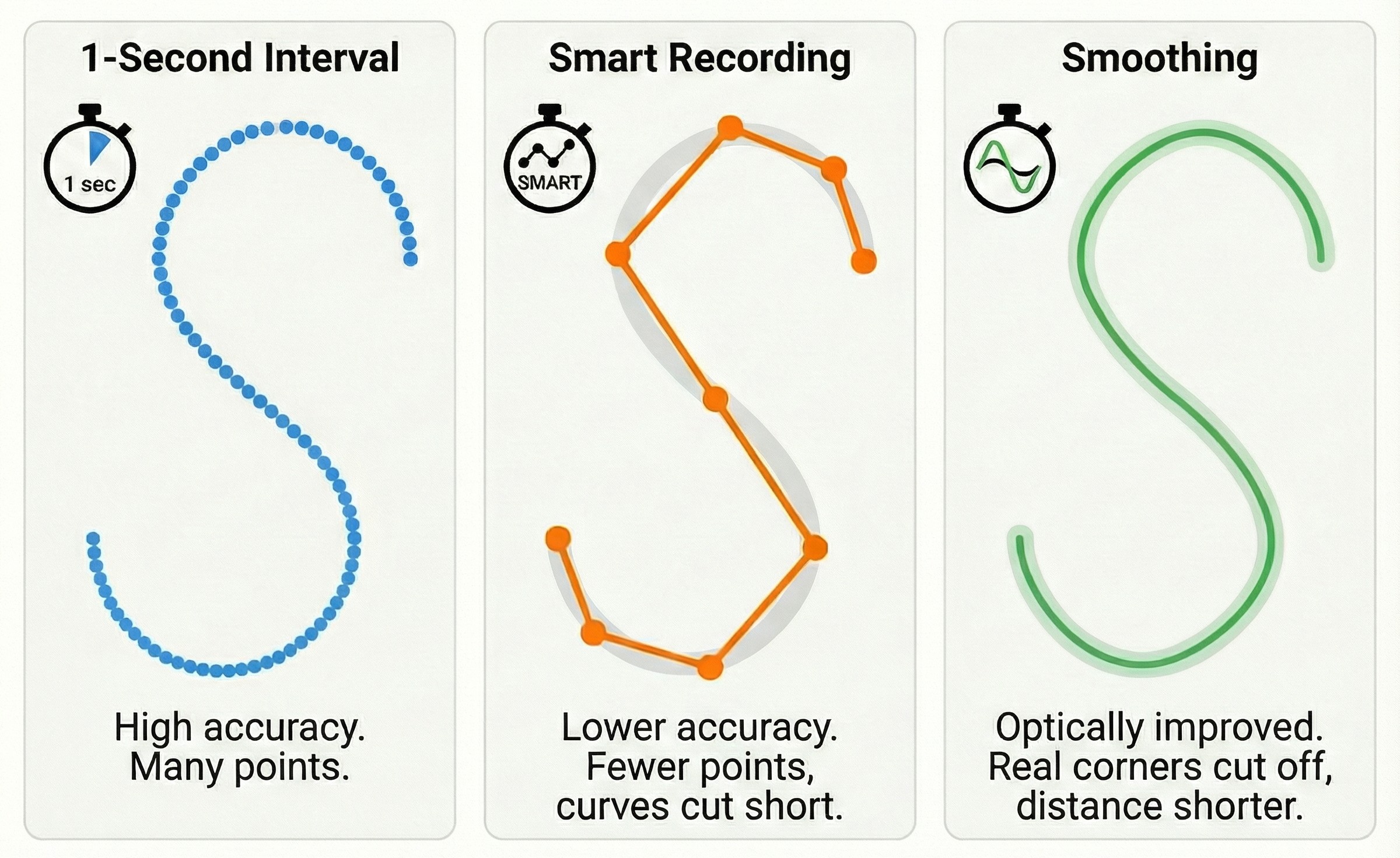

- Sampling rate and recording interval: Sports watches log a GPS point every second as standard (or at least offer the option to do so). This results in a dense track recording that closely traces the actual route. Smartphones and fitness apps, on the other hand, often use adaptive sampling rates to save battery power—e.g., position every 4–5 seconds or depending on the distance/speed covered. Less frequent updates can lead to a "more angular" track and slight distance deviations, as a straight line is simply assumed between two points. Many sports watches also offer a power-saving mode, but 1-second logging is standard in normal cases. In short: a cell phone may be sufficient for steady movements, but for interval training, lots of turns, or stop-and-go, a sports watch often records the details more completely.

Today's smartphones are amazingly accurate and, thanks to multi-GNSS, perfectly adequate in typical situations (jogging in the park, cycling on bike paths). The differences become apparent in extreme conditions: anyone who is out and about in difficult terrain or wants their performance data to be as accurate as possible will benefit from the specialized hardware components, algorithms, and sensors of a good sports watch. These watches are built to log GPS continuously, even for 5 hours at a time, and deliver stable results—whereas a smartphone is primarily a communication device that handles GPS as a side function and makes more compromises (energy saving, everyday use). Last but not least, battery life plays a role: a sports GPS can usually track for 10+ hours, whereas a cell phone battery may run out before then. On the other hand, you almost always have your smartphone with you. So it depends on the application – for important competitions or mountain tours, ambitious users usually rely on dedicated devices because they value their reliability.

Influencing factors: Typical sources of error and accuracy

No GPS track is perfect—a wide variety of environmental and signal conditions can affect measurement accuracy. Here are the most important influencing factors and sources of error that explain why a track can sometimes be inaccurate:

- View of the sky: GPS works best with a clear view of the sky (at least 15° elevation above the horizon all around). Tall buildings (urban canyons) block or reflect signals – in city centers, the position therefore often "jumps" or can be offset by tens of meters. Natural canyons and valleys have a similar effect: between mountain flanks or in narrow valleys, often only a small section of the sky is visible, so fewer satellites are available and the signal is reflected off rock faces. The result: poorer accuracy or temporary signal loss.

- Dense forest and canopy: Trees significantly attenuate GPS signals. In forests—especially those with wet leaves or coniferous trees—the signal can be weakened to such an extent that positional accuracy decreases or the device only receives irregular points. In addition, dense tree canopies cause multipath effects, as the signals are refracted by branches. Good devices can partially detect this and filter out the noise, but a deviation of a few meters is normal in forests.

- Indoor spaces, tunnels, underpasses: GPS signals hardly penetrate roofs. In buildings, there is usually no reception—smartphones may then resort to Wi-Fi/mobile phone location tracking, but this is useless for tracking. GPS fails completely in tunnels or subway stations. Sports watches ideally pause distance measurement or extrapolate via sensors (pedometers) in the tunnel. Nevertheless, GPS tracks through tunnels often result in straight lines (between the last and next GPS point), which of course do not correspond to the actual route.

- Shading by bodies or objects: Interestingly, even the human body can shield GPS signals, as it consists of ~70% water (water absorbs microwaves). For example, if you carry a cell phone in your hand and hold it close to your body, or if you run in a dense group of people (e.g., marathon starting block), reception may deteriorate. Garmin explicitly mentions "using GPS in a dense group of people" as an accuracy problem. This explains why the track sometimes fluctuates at the start of a race—hundreds of runners around you block part of the satellite view.

- Multipath reflections: As already mentioned, reflections off hard surfaces (buildings, rocks, bodies of water, large vehicles) cause multipath errors. This means that the receiver detects a signal from the wrong direction with a delay. A typical symptom is that the route being plotted suddenly "jumps" to the wrong location or shows a deviation from the actual route until the signal recovers. In cities, for example, you can see tracks that jump alternately from one side of the street to the other—caused by reflections on glass facades. Dual-band devices and multi-GNSS help here, but the problem can never be completely eliminated.

- Satellite geometry (GDOP): Not only the number of satellites, but also their position influences the quality of a position solution. Ideally, the available satellites are nicely distributed across the sky (e.g., one far north, one south, one east, one west above) – then the geometric distribution is wide and the so-called DOP value (Dilution of Precision) is low. If the satellites happen to be unfavorably positioned (e.g., all on one side of the sky), accuracy deteriorates significantly, even if reception is available. This phenomenon explains, for example, why better GPS data is possible at some times in one location than at other times (the satellites are orbiting, after all). Professional applications calculate the GDOP and wait for a better "window" if necessary. This is less noticeable in sports devices, as they always use many satellites at the same time (multi-GNSS reduces the risk of poor geometry here).

- Atmospheric effects: The ionosphere and troposphere can slow down or deflect GPS signals (refraction). Ionospheric delay depends on the time of day and solar activity and can lead to errors in the meter range. Simple receivers make rough corrections using a model, but dual-frequency receivers measure the delay directly (see dual band) and greatly reduce this error. Weather conditions (heavy rain, thick clouds), on the other hand, have little effect on GPS in the L-band—the signal penetrates clouds almost unhindered, unlike satellite TV, for example, which fails in heavy rain.

- GPS drift and noise: Even under ideal conditions, a GPS position is never completely accurate, but always fluctuates slightly around the true value. With good devices, this background noise is in the range of 3–5 m. Manufacturers such as Garmin specify an accuracy of ~3 m in 95% of measurements for sports watches. These small deviations lead to the phenomenon of GPS drift: when you stand still, the recorded point slowly "wanders" around. To the user, this may look as if the track is jumping back and forth for no reason. In addition, the device may add up these minimal position changes to the distance – so that you continue to "cover" meters while standing still. Garmin states that with normal GPS drift, up to 180 m of distance can be incorrectly counted per minute of standstill if you do not pause the recording! This numerical example illustrates the influence of noise. In practice, many devices mitigate this by stopping distance counting below a certain speed or offering an auto-pause (see Interpretation). Nevertheless, a few meters of inaccuracy per kilometer are completely normal.

So how accurate is GPS tracking? Under optimal conditions (clear view, multi-GNSS), you can assume ~3 m horizontal accuracy. In dense cities or forests, deviations can increase to 10 m or more. Altitude data from GPS tends to be less accurate (often ±10 m or more) due to the less favorable geometry – a calibrated altimeter significantly improves the situation here. Overall, experience shows that distance measurement on running watches has an error margin of 1–3%. This means that an officially measured 10 km run is often recorded as ~10.1 km (slightly "too long"). This slight overdistance is caused, among other things, by dozens of small zigzag deviations (systematic overestimation). Important: These are typical deviations, not guarantees – depending on the circumstances, it can sometimes be better (or worse). However, with the following tips, you can get the best possible accuracy from your device.

Why are dual-band and multi-GNSS important for athletes?

Anyone who is ambitious about sports—whether it's trail running in the mountains, cycling in the forest, or city marathons—will benefit from the modern GNSS features Multi-GNSS (multiple satellite systems) and dual-band (multiple frequencies). Here are the reasons why these technologies are so relevant in a sports context:

- Better reception in difficult environments: When doing sports, you are not always in open fields. Runners and cyclists in particular often traverse varied terrain – today a park avenue, tomorrow a urban canyon, the day after tomorrow a mountain trail. Multi-GNSS ensures that as many satellites as possible are always available in the sky. If the device enters a shadow area, Galileo or BeiDou may still provide signals from a different angle. This increases the availability of the signal. Dual-band, in turn, keeps the position solution stable, even if reflections occur or the ionosphere has a strong influence, e.g., in the mountains. The position drifts less and remains more accurate where single-band receivers might lose accuracy. For athletes, this means that the track is recorded continuously, even in otherwise problematic passages (dense forest, city center), and large outliers are reduced.

- More accurate pace and distance measurement: Athletes pay particular attention to precise pace data, especially during intervals or competitions. However, if the GPS is inaccurate, the current pace may jump around or the distance may be incorrect at the end. Dual-band GPS offers significantly more consistency here. Without dual band, there is a higher probability that curves will be cut off and the distance shortened – which would be fatal, for example, on a trail run with many switchbacks, if the watch measures 1 km less at the end. Multi-band GNSS provides clean route coverage so that pace data and split times are accurate. Sports watches with dual band also show smoother pace values in the city center, for example, while older models tended to jump from 4:30 to 6:00 min/km just because the signal suffered briefly. This is a big advantage for ambitious runners, as training successes can be measured more accurately.

- Fewer "GPS dropouts" in recordings: Everyone knows the feeling—when analyzing your run, you suddenly find a spike where you supposedly ran through the lake or shortened your route by 100 meters. Multi-GNSS and dual frequency significantly reduce such gross errors. Of course, errors can still occur, but the robustness increases. Especially in longer endurance events (ultra runs, marathons), small inaccuracies add up. With high-precision GNSS, you end up with a more accurate total distance. This can mean the difference between victory and defeat, for example in navigation races (keyword: orienteering – here, every meter counts).

- Future-proof: The GNSS world is constantly evolving. More Galileo satellites are coming, GPS is activating new signals, and services such as the European correction system EGNOS are improving accuracy. A device that is multi-GNSS-capable can take advantage of these improvements. Many current watches, for example, allow new satellite systems to be added via firmware. For athletes who use their device for several years, this is a plus—you are ready for future accuracy improvements.

In summary: Multi-GNSS + dual band = maximum position quality, which increases track accuracy and metric precision, especially in sports. So if you train a lot in challenging environments (big cities, trails) or simply want the most accurate track, you should consider a device with these capabilities. In the next section, we'll take a look at how track recording can be influenced (keywords: recording interval and smoothing).

Track recording: Smart Recording vs. 1-second interval & smoothing

In addition to pure GNSS technology, the type of data recording also plays a role in the accuracy of a track. Two important aspects here are the recording interval (regularly every second or "smart") and subsequent smoothing/filtering of the track.

- Smart recording vs. 1-second intervals: Some sports watches (and older GPS devices) offer a mode in which not every second is recorded, but only "important" points. Historically, the aim was to save storage space and extend battery life. In smart recording mode, data points are logged at irregular intervals – only when certain criteria are met. For example, the watch saves a new point when it detects a noticeable change in direction of movement, or when speed, heart rate, or altitude change significantly. If you continue straight ahead at a constant pace for a while, fewer points may be set. Although modern devices have sufficient memory, Smart Recording is still available as an option (or standard) for compatibility reasons. Disadvantage: fine details may be lost by omitting points. In particular, start/stop points or sharp turns could be "rounded off" because no point was saved at that exact location. This leads to small distance errors—for example, a Smart Recording track may shorten a 90° turn to a slight diagonal. This may hardly be noticeable for everyday runners, but in competitive segments it can affect timekeeping. That's why experts often recommend setting the recording to 1 second, provided battery life and memory allow it. This is usually the default setting on new watches, while older Garmin devices sometimes ran in smart mode by default. Incidentally, thanks to efficient chips, 1-second logging now consumes hardly any noticeable battery power, so the historical advantage of smart recording is almost obsolete.

- Smoothing algorithms: One aspect that is less obvious is how the recorded GPS points are connected to form a route and possibly smoothed. Viewed in isolation, successive GPS fix points could result in a wild zigzag pattern because the signal deviates slightly from the actual value. Many sports watches and apps therefore use a smoothing algorithm to improve the track visually and metrically. Specifically, they attempt to reconstruct the probable actual movement from the sequence of points. A simple method is to average out small outliers to create a reasonably smooth path. The problem is that if you smooth too much, you can "miss" real changes in direction. The watch might assume that you are continuing to run straight ahead, even though you have actually turned – until the deviation becomes large enough and the software "notices" that there was a curve after all. Then the curve may be cut off in the track. One example is 400-meter running tracks, where athletes run tight curves. Many GPS watches tend to record distances that are too short on the track (e.g., 390 m instead of 400 m per lap) because the smoothing algorithm does not fully detect the tight changes in direction and shortens the corners of the laps. On the other hand, smoothing prevents the track from shaking back and forth like a "drunken zigzag course" when running straight ahead. So it's a balancing act. The exact functioning of the filters is usually a trade secret of the manufacturers, but the following can be observed: Garmin smooths moderately (in some cases, distances are measured slightly shorter), Polar smoothed more in older models (which led to noticeable under-distance), and Apple even uses AI models in the Watch to optimize the track retrospectively. Important to know: Smoothing affects track display and distance measurement. So if your recorded route runs very "cleanly" along a road, an algorithm may have helped (such as map matching on the road layer, which many navigation apps do). For sports watches, however, manufacturers try to strike a balance: on the one hand, suppressing noise, and on the other hand, not distorting real movements.

Example: Smart vs. 1s vs. smoothed: Let's say you're riding your bike and maintaining a steady pace on a winding mountain pass. A watch in 1s mode sets a point every second – the track will resolve the curves finely. In Smart mode, on the other hand, the device may only set a point at each major turn; in between, the route is interpolated as straight – in extreme cases, serpentines could be "cut." If strong smoothing is then applied, the curve radii could be further straightened. The result: the total distance is measured noticeably shorter than it actually is. For precise evaluation, you should therefore always use 1s logging. Smart Recording is intended more for occasions where memory is limited or the route is irrelevant (practically no longer a scenario today).

Fortunately, many newer devices have done away with smart recording or hide it deep in the menu. If your sports watch offers this option, it is advisable to set it to "every second" – the battery drain is minimal and the data quality is higher.

Interpreting GPS data: jumps, shortcuts, and other anomalies

When analyzing your recorded GPS tracks (whether on Strava, Garmin Connect, or another platform), you may occasionally encounter unusual track patterns. Here are a few typical phenomena and tips on how to interpret them:

- Accept slight distance deviations: GPS is never 100% accurate. It is normal for an officially measured run (e.g., 5.00 km) to appear as 5.05 km or 4.95 km on the watch. Typically, the deviation is around ±1% of the distance. This does not mean that the distance is wrong or that the device is "bad" – it is simply measurement inaccuracy. In competitions, many organizers factor in this tolerance (most running watches measure slightly too much). So don't panic if your marathon watch shows 42.8 km – you haven't run "too much," the GPS has just added a little extra.

- Sudden GPS jumps in the track: Sometimes you will see sharp spikes or teleportation-like shifts in the route. These are usually caused by signal errors such as multipath reception or brief signal loss. In city centers, for example, the GPS may jump to a parallel side street for a few seconds (reflections from buildings). Such outliers can often be recognized by the fact that unrealistically high speeds were calculated for a short time (e.g., 100 km/h jogging speed). A single jump can be removed from the route later (many portals smooth this out automatically). It is important to know that such jumps are technical artifacts, not real movements. So if your track crosses a rooftop even though you were running on the street below, the signal was briefly insufficient. Dense buildings and tunnels in particular cause such errors. In this case, it helps to wait a few seconds until the signal has stabilized, if possible.

- Cut corners and shortcuts: If your recorded route smooths out curves (as if you had driven/run through the inside of the curve), this is either due to insufficient point density or algorithm smoothing (see previous chapter). Especially with older recordings with 5-second intervals, it can happen that serpentines, for example, are only roughly angular – the device simply did not capture the shape with enough points. Strong smoothing can also shorten corners. Interpretation: Your actual distance was slightly longer than the track. This doesn't matter for orientation purposes, but you need to keep it in mind for accurate speed calculations. However, modern watches in 1-second mode hardly cut corners anymore – if they do, it could be due to aggressive filtering (some platforms allow you to display "original data" vs. "smoothed" data).

- "Snake line" despite a straight route: Conversely, there are cases where you have actually run in a straight line, but the track shows small deviations. This is usually GPS noise, meaning that the signal has varied slightly, which the track displays as a zigzag. This is often seen when walking slowly or in the forest: the track wobbles left/right around the path. These zigzag lines can lead to a slight overdistance because the back and forth is counted as extra meters. Many algorithms smooth this out (fortunately) to some extent. However, if you have a very shaky track, the reception may have been poor. Tip: In dense forests, hold the watch away from your body (e.g., attach it to your backpack shoulder strap) so that it has a better view. This can reduce the zigzagging.

- GPS drift when stationary: As described above, the GPS position moves slightly even when stationary. So if you stop for a longer period of time during a recording (pause at traffic lights, enjoying the view, etc.), your track may draw a circle or a chaotic pattern at the point where you paused. This can also result in incorrect distance being added. Tip: Use the auto-pause function on your sports watch (if available) during breaks or stop the recording manually if accuracy is a top priority. This will prevent 5 minutes of standing still from being rewarded with 100 m of "movement." Restart after you start walking again—modern devices usually pick up the GPS signal again quickly.

- Question altitude data: GPS altitude readings should be interpreted with caution. If your watch does not have a barometer, the recorded ascents/descents can be massively inaccurate—for example, a flat run may suddenly show a +200 m elevation gain, even though there was hardly any uphill running. This is due to GPS altitude drift and errors in altitude calculation. Sports platforms such as Strava sometimes offer elevation data correction: your GPS track is compared with a terrain model to obtain more realistic elevations. However, if your watch has a barometric sensor, it is better to trust this data – it is usually more accurate as long as the sensor has been calibrated. Check whether your device automatically calibrates altitudes (often via GPS at the starting point or via known POIs). Interpretation tip: Small bumps in the altitude profile may be noise; focus more on the total altitude meters. For example, if you are running on flat terrain and the watch shows +50 m, you can ignore this – it was GPS noise.

- Comparison with the map: A useful trick for interpretation is to view the track on a satellite map or route map. Many deviations can be put into perspective when you see: "Ah, the point is next to the road, but that's because of the urban canyon." Smartphone apps in navigation mode often "snap" the marker to the nearest road to conceal this from the user. However, nothing like this is corrected in the recorded track—it shows the raw (or only slightly smoothed) GPS data. So if something looks totally implausible, it's usually an error, not a miraculous teleportation. Compare several laps if necessary: if there is always a jump at the same point, it is probably due to a local interference factor (lots of metal roofs? Radio mast?).

In short: know the limits of your GPS data. A track is never perfectly accurate—it is an approximation. For most purposes (tracking your route, logging your training), the precision is high enough. But you shouldn't overinterpret every little blip. If something looks strange, it's usually due to a technical reason. And if you need maximum accuracy, use the tips mentioned above: good visibility, allow time for signal fix, use dual band in difficult sections, use the pause function, etc. Then you'll get the best possible data.

What makes good GPS tracking hardware?

Finally, let's summarize what's important in good GPS tracking hardware—whether for your next sports watch or smartphone:

- Multi-GNSS support: A modern device should be able to access multiple satellite systems (GPS, Galileo, GLONASS, BeiDou). This significantly increases satellite coverage and reliability, especially in urban or difficult environments. Multi-GNSS is now standard in almost all current mid-range and high-end smartphones and sports watches.

- Dual-band GNSS (multiband): Dual-frequency reception is a major advantage for maximum accuracy. Good sports watches from 2022 onwards will offer dual-band GPS, which provides measurably more accurate tracks and reduces problems such as ionospheric errors and multipath. Anyone who values very accurate pace and distance (e.g., competitive or trail athletes) should opt for a dual-band-capable watch.

- High-quality antenna and reception design: Even the best GNSS electronics are of little use if the antenna is poor. High-quality devices can often be recognized by their sophisticated antenna design—such as ceramic patch antennas or metal watch bezels that serve as antennas. These enable stable reception even in difficult locations. A smartphone in a thick protective case or attached to your arm can be a disadvantage here. So pay attention to user reviews on the GPS reception quality of a device.

- Barometric altimeter: For anyone who tracks altitude (runners, cyclists, hikers), a built-in barometer is a must. Good sports watches have a barometric sensor that automatically syncs with GPS. This provides reliable altitude readings and prevents inaccurate measurements due to GPS altitude drift. You'll notice the difference immediately when running in mountainous terrain or up stairs.

- Sensor fusion & algorithms: Top models rely on smart software: They filter GPS data, use motion sensors to supplement it, and have features such as automatic pausing and intelligent recalculation. These algorithms contribute greatly to the final quality. A "good" GPS watch, for example, uses a gyroscope to recognize that you are running on a 400-meter track and provides distances that are almost track-accurate (Garmin Track Run feature). So, if you're looking for precision, pay attention to features like these.

- Flexible recording interval: Ideally, the device should log data every second or at least offer this option. Some newer models select this dynamically (e.g., SatIQ). It is important that you do not lose accuracy due to incomplete logging. Good devices therefore do not use rigid smart recording or only use it if the user wants it (e.g., in Ultratrac battery mode).

- Battery life and performance: An outstanding GPS tracking device strikes a balance between accuracy and endurance. Dual-band and multi-GNSS place greater demands on the battery, but high-end watches such as the Garmin Fenix or Coros Vertix still deliver over 20-30 hours of runtime in full GNSS mode. This is a feature of good hardware—it uses energy-efficient chips and large batteries. Especially important for ultras and multi-day tours: in energy-saving mode, the watch should still offer acceptable recording quality (e.g., via FusedTrack or similar).

In summary, good GPS tracking hardware offers: reception strength, precision (through multi-GNSS/dual band), additional sensors (barometer, gyro) for complete information, smart software for data processing, and sufficient battery life for your longest sessions. The current generation of sports watches and high-end smartphones has made enormous progress in this area. For example, high-quality running watches today often achieve an accuracy of ~3 m under good conditions – a value that seemed utopian in the consumer sector just a few years ago. For you as a user, this means that you can largely rely on your track recording. Of course, GPS remains a radio system and not a millimeter-precise measurement system – but with the right device on your wrist, your runs, bike rides, and hikes will be tracked reliably and accurately, allowing you to concentrate fully on your sport. Have fun training – and may you always have good GPS reception!